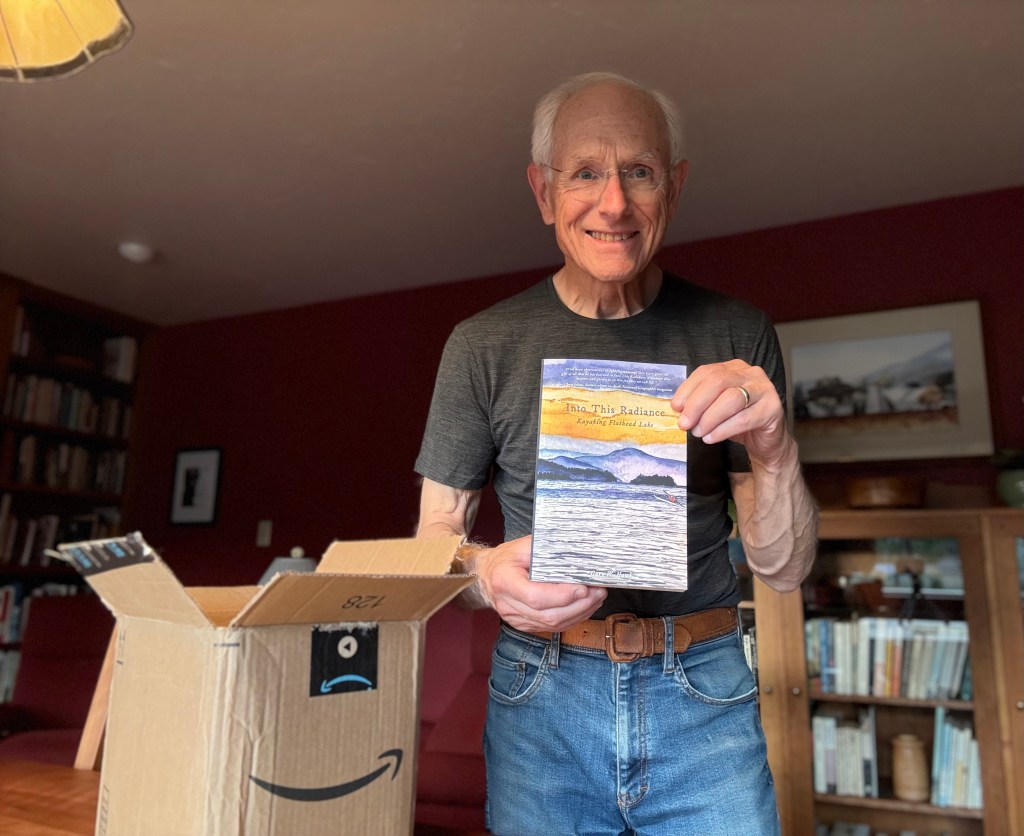

I wrote a book based on my experiences in a kayak on a huge, ever-changing lake. Because I believed in what I had written, and that a portion of my life could be expressed in language, I felt a responsibility to face the public.

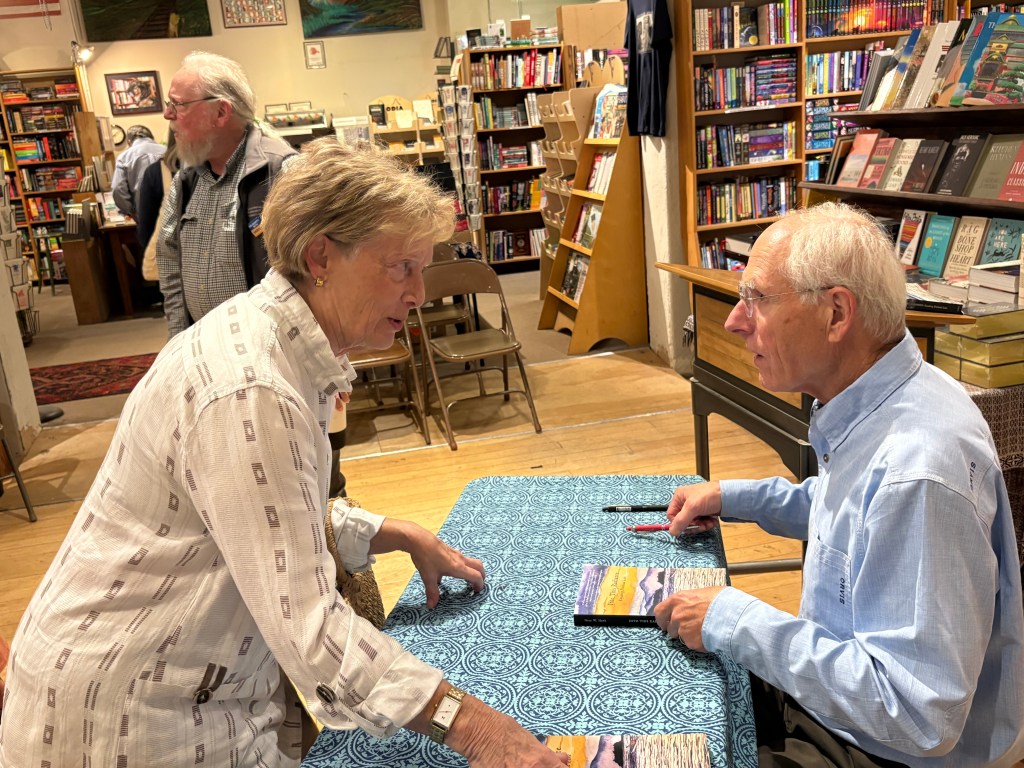

I have read twice now, once in a bookstore and once in a public library. A couple of other events hang on the calendar. I have learned something important, something I did not expect. On the surface a public reading can interest attendees in a book and a few copies might be sold. But I now see clearly that drawing attention to a book is not the purpose of the event.

On both occasions before different kinds of audiences, conversations flew through the air like October’s leaves yanked from stems by gusts of wind. The reading of an essay stimulated activity in the minds of listeners and helped them connect with their own experience. Suddenly this usually silent and invisible mental activity became visible and audible. People began to tell stories about their own encounters with light and sound, waves and wind, stories about friends they have loved and lost, things they make, things they have done and hope to do if given the time. The room began to sparkle with ideas and interaction. People spoke not just to the author but to each other.

Reflecting on these experiences I have concluded that people are hungry for interaction, seem eager to be heard by anyone who stands still long enough to hear a story or pay attention to a question. I do not know if this need is the lingering aftereffect of the pandemic and imposed isolation or, if in fear of the other, we have held ourselves back from interaction because we anticipate criticism or conflict. Whatever the reasons, I witnessed a great desire to speak and feel heard.

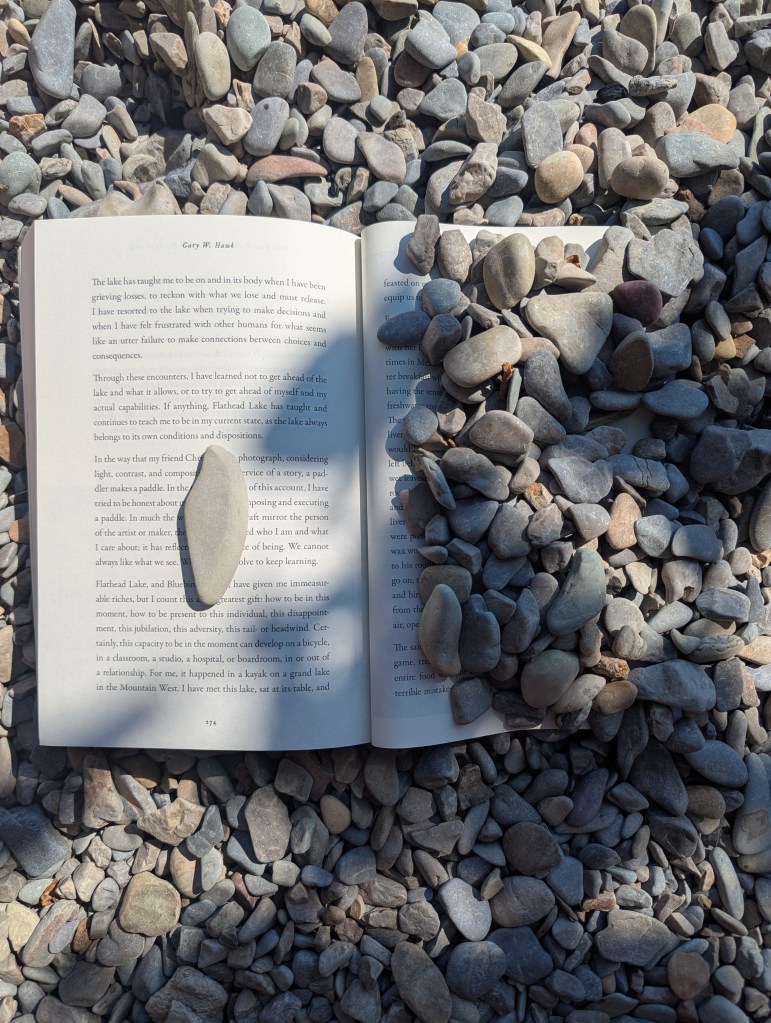

I learned an equally important thing. The second event was held in the public library in Polson, Montana. It seemed as if people in the community knew that a library is a safe place for all kinds of people, almost as though an unwritten covenant guides behavior and brings people together in a common purpose. To be sure, this sense of safety and openness is fostered by the librarians, their knowledge, warmth and hospitality. But I had never seen so clearly the value of a library to a community, especially in a small town. A library or an independent bookstore fills minds and hearts with fresh ideas, awakens generosity, and makes clear that not every contact is driven by the repetitive and reinforcing loops of algorithms.

On both occasions a writer became a listener.