Near the end of March it is still snowing, not in the fitful fashion of a spring squall but continuously, earnestly, as it usually snows in December. Once again the driveway is covered in snow and the back slope wears an armor of ice. We have been locked inside this winter for five solid months. Yet, the expansion of the light after the equinox has an effect on me in the same way that it normally affects the apple tree outside the south window. In a normal year, whatever that is, the buds would be swelling by now in response to the light if not the weather. Despite the weather, something in me is also awakening. Despite the snow and unseasonable cold, I am beginning to imagine paddling my kayak, negotiating wind and waves in a glassy vessel, exploring islands and coves, immersing myself in color, dissolving into the life of the lake.

This weather that keeps me indoors also leads me to reach toward my shelf of favorite books where I find The Living Mountain by Nan Shepherd, a slim, white paperback that stands in the company of hardbound Wendell Berry, Annie Dillard, Robin Wall Kimmerer and Robert Macfarlane. The book tells the story of Shepherd’s first sight of the Cairngorn plateau in Scotland when she was a child and how it awakened a desire to explore its heights and depths. She recounts encounters with wild weather and hardy human beings. She traverses slopes, climbs peaks, notes birds, animals and insects, crosses streams confined by granite walls, traces their courses from uppermost springs to the valleys of the Spey, Avon or Dee.

First published in 1977 by Aberdeen University Press, the book was written in the years during and soon after WWII. After Shepherd received a discouraging response to the manuscript she tucked it in a drawer where it sat untended for almost thirty years. Meanwhile she continued to climb and explore her living mountain, but also the mountain that had impressed itself on her mind and heart. In a disturbed and uncertain world the Cairngorns were her “secret place of ease.” Then as an old woman she began “tidying out my possessions,” as she says. Rereading the manuscript, she found it still valid and felt renewed energy to see it published. We are so much the richer for the second wind of this writer and her belief in what she had written.

In some ways the book resembles a kitchen pantry nearly bursting with sensory detail. As Shepherd opens the door on this pantry, she describes the taste, touch, smell, sights and sounds of the mountain in all seasons of the year, both night and day. With her description of the taste of a berry, the texture of a plant or stone, what it feels like to walk barefoot over heather, the sound of an owl landing on a tent pole or a storm crashing into the walls, canyons and corries, she practically places us inside the mountain. Then in the final chapter, acting as our mountain guide, she takes us beyond all the details of weather, the colors of leaves and feathers, the varieties of animals, the intricacies of trails and routes, human pleasures and fatalities. She leads us up and out, or down and in, until we break into the open to consider the deepest things of all, the mystery of what it means to be alive, to be aware of one’s own being in the company of Being itself. It is as if the fog and mist of sensory detail suddenly clear and in her company we see an open sky above the summit.

Rereading the final chapter of The Living Mountain I realize that what Nan Shepherd says of her beloved range might easily be said of Flathead Lake. One only needs to change a few words from her closing paragraphs to experience the lake that, like her mountain, is its own living being. If she had lived in Montana instead of Scotland, when she crested the last moraine heading into Polson she might have written:

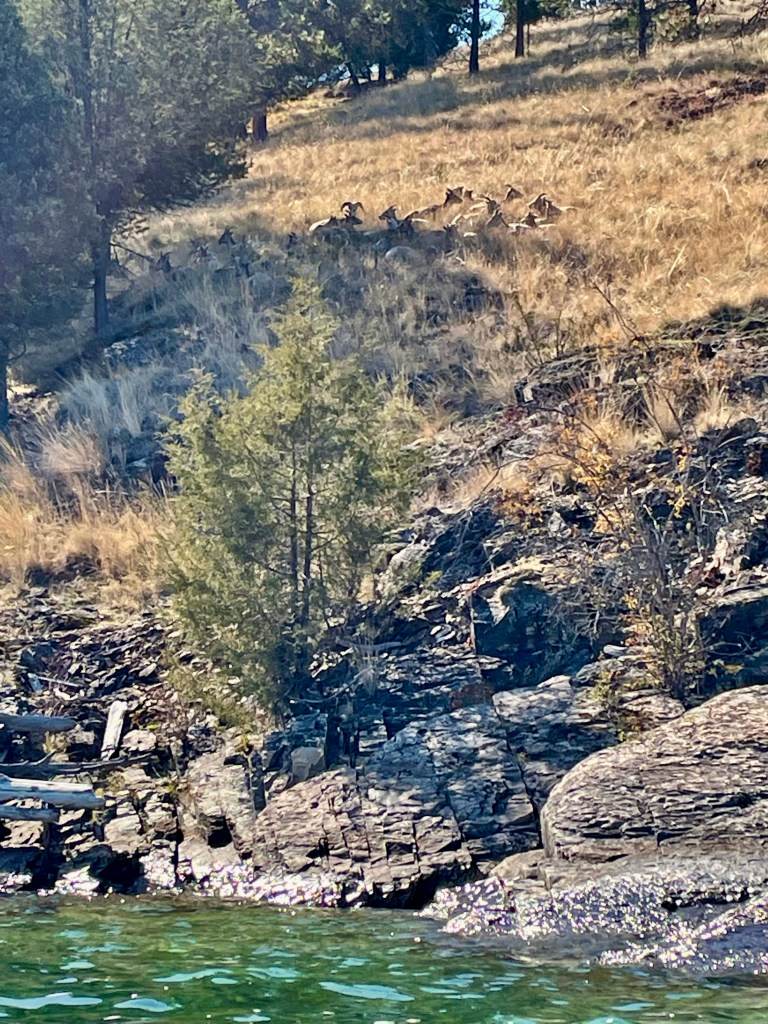

…So my journey into an experience began. It was a journey always for fun, with no motive beyond that I wanted it. But at first I was seeking only sensuous gratification—the sensation of height, the sensation of movement, the sensation of speed, the sensation of distance, the sensation of effort, the sensation of ease: a kind of lust of the flesh, the lust of the eyes, certainly the pride of life. I was not interested in the lake for itself, but for its effect upon me, as (a cat) caresses not the man but herself against the man’s pant leg. But as I grew older, and less self-sufficient, I began to discover the lake in itself. Everything became good to me, (its long shoreline, its islands, its rocky hillsides and forests, its shades of color, its crevice-held flowers, its birds). This process has taken many years, and is not yet complete. Knowing another is endless. And I have discovered that the experience enlarges (the ramps and slabs of stone, deep, dark depths, turquoise shallows, great banks of gravel, deer and sheep drawn to the margins). The thing to be known grows with the knowing.

I believe that I now understand in some small measure why the Buddhist goes on pilgrimage to a mountain (lake). The journey is itself part of the technique by which the god is sought. It is a journey into Being; for as I penetrate more deeply into the (lake’s) life, I penetrate also into my own. For an hour or two I am beyond desire. It is not ecstasy, that leap out of the self that makes a human like a god. I am not out of myself, but in myself. I am. To know Being, this is the final grace accorded from the (lake).

I do not know when this storm will end, when the ground will thaw, when the water temperature will rise enough to make paddling seem safe. But as the light changes, whatever atmospheric rivers flow our way, I imagine what it will be like to be on and in the living lake. Like Shepherd the hiker and climber, walking herself “transparent” to every living thing in her world, I hope to paddle myself transparent, clear of fears and concerns, empty of self, open to every resonating thing in a still-living world. As Shepherd’s knowledge of the mountains evolved, so, too, has my motivation and knowledge of the lake evolved. I will return to the lake not for myself but to experience the lake being itself.