Subscribe to continue reading

Subscribe to get access to the rest of this post and other subscriber-only content.

Subscribe to get access to the rest of this post and other subscriber-only content.

I was determined to go paddling before the thermometer popped the 100-degree mark, before fires grew worse and the air became unhealthy from fires to the west and south. Having paddled in honor of my mother in May, and having introduced one of my granddaughters to the lake and its largest island in June, I wanted to paddle within myself in July, returning to places that are no longer new.

With the smoke in a blue-gray band above me, I stroked out of the marina at Finley Point, made a right turn and headed for Bird Island. I quickly fell into that beautiful rhythm of harmonious breathing timed to the pace of my strokes. Though I have made this paddle countless times, something about the island was different. Through the haze I could see that Montana’s Fish, Wildlife and Parks had installed a solar toilet near the south end of the island, above the beach where many people come ashore. I applaud their decision to reduce waste on the fragile island. Continuing north I saw the black blocks of stone that mark the entrance to one of my favorite coves near the opposite tip of the island. Rounding this angular corner I saw a cove I hardly recognized. Instead of a little bay with an incredible view and an accommodating beach, this half circle of shelter was choked with logs that had washed down from the north, trees that had fallen since the island burned, a massive, bleached post, and lots of lumber ripped from docks, nails in the air. There was barely enough room to slide my kayak into a secure position while I walked over the debris and dove into the water from one of the blocks of stone.

Refreshed by my plunge and a little hungry, I ate a peanut butter and jelly sandwich and a couple of delicious rolls of baklava left over from a party we attended Sunday night. Since the lake was calm and with no change in the forecast, I decided to try something I had never done before—paddle from Bird Island across the width of the lake to Wild Horse Island. As often as I have paddled to Wild Horse, I had never made this eight-mile crossing. I drank half a water bottle charged with electrolytes and settled into a sustainable pace. In the thick haze it was hard to pick a target that would keep me moving in a straight line, but I aimed for a faint wedge of shade on the northeast corner of the island.

The miles seemed to fly by as I concentrated on rhythmic strokes. In mid-July the surface of the lake is usually clean; pollen has settled onto the bottom and tree roots and branches have come ashore. But this year the surface of the lake was covered with a yellow substance that I first thought was pollen, but then realized was dried algae. Throughout the crossing I made small adjustments to my course to avoid floating woody debris, branches, roots and bark. Eventually, it dawned on me that this year’s high lake level had lifted material from beaches and riverbanks across the watershed and set it in circulation. This was a different lake surface.

When I finally landed in a small indent on the east shore, I was sweaty from the effort. Not hearing the sound of boats and their engines, I stripped my clothes, left them to dry on hot stones and made a few breaststrokes out into the viridian. I thought to myself, all of us should swim naked more often and not leave this experience to children exploring water for the first time.

Curious about this part of the island, I dressed again and began to explore the forest above the narrow beach. I found a premier pink Mariposa lily. Having once found several white ones, I regretted having once mislabeled this plant as a sago. I also found a dead raven. Though I could not be sure–since the breast of the bird had not been consumed—I wondered if the big black bird had been knocked out of the sky by the fist of an eagle.

Back at the beach I found half of a broken stone that because of its color and dimensions reminded me of a cookie, but then found its other half in another location. I tested the fit and found it perfect. I think I have an eye for cookies. Together the stones reminded me of the ancient Jewish practice of cutting a covenant or the practice in English jurisprudence of cutting a contract. Once again, I realized that a familiar place seen with fresh eyes can be full of discoveries.

I returned to Bluebird, ate a wedge of my favorite Manchego cheese, salty crackers and the last of my baklava. In planning my return to Finley Point I decided to paddle down the east shore, cross to Matterhorn Point, then Black Point, the east side of the unnamed island in The Narrows, then cross to the last spindly cottonwood marking the mouth of the marina at Finley campground. This route would give me a brief period of shade every time I passed a point or island. In the heat of late afternoon I craved shade. I added sunscreen, filtered another bottle of water, ate a dried apricot or two, and settled into the next leg of my journey.

When I finally landed at the concrete boat ramp at the marina a woman came rushing up to me.

“Was that you way out in the middle of the lake? We watched you come across.

“Yes,” was all I managed to say, tired from almost 27 miles of paddling and not quite ready for human interaction after seven hours of solitude.

Strangely eager, she asked, “Would you like some help lifting the boat out of the water?”

Never before had I accepted such help, but conscious of many new things in a place that has become familiar, I stretched myself and said, “Sure. That would be wonderful, but we need to set the boat on the grass so I can unload my emergency gear.”

This friendly and strong woman seemed to enjoy offering this assistance and I confess to being grateful for her help. After we set the boat away from the concrete she said, “My husband and his friend will come over and help you lift your boat onto the saddles of the rack.” Not quite at ease with this change in myself, I simply said, “Great.”

I piled wet gear, emergency bag, phone in its Pelican case, and first aid supplies in the bed of the truck. Turning around I saw two guys coming toward me asking for directions. One carried my Greenland paddle that I had tossed on the grass. The other lifted the bow into the back saddle and helped me slide the boat forward into place. It was a joy to have help. This was as much a discovery as the changes to my favorite cove, the pink lily and the raven. All that was new was beginning to find a place in a life I know by heart.

On Father’s Day I am still thinking about taking my oldest Pennsylvania granddaughter paddling on Monday, June 10. Bodhi spends time in the gym, treadmills at a steep angle and lifts weights. She is broad-shouldered and almost as strong as her father. Even though most of her paddles take place on the lazy Brandywine where she and her sister look for turtles, I thought she might be able to paddle from the Walstad access to Skeeko Bay on Wild Horse Island.

After pulling into the parking lot, I walked down to the dock, the lake now full as my wife’s coffee cup. I saw conditions like those predicted by the NOAA site I faithfully consult—winds out of the southwest at 15 mph, waves less than one foot, locally up to two feet. The only catch was that we would have to contend with quartering seas that would consistently push us off our compass point.

We laid out our gear and placed the boats on softer ground than the concrete handicapped pad. I offered my boat to Bodhi, a little more stable and faster than my old plastic Perception Carolina 14.5. When she accepted the invitation, I put my head inside the tunnels to adjust four foot pedals. On the second try I got them right. Because of the wind I also suggested that we wear our blue paddle jackets.

I nudged her off the ramp and told her to hang out and get a feel for the boat while I made ready to launch. At first, she felt uneasy with the rolling motion as waves pushed her port stern quarter, so we advanced slowly into the lake, giving her time to adjust herself to the conditions. I could tell that she felt anxious because she paddled hard and fast, as if eager to get to the island. In the shorter, heavier boat I found it difficult to keep up with her. We worked in manageable conditions for a little less than an hour, but the waves kept knocking her away from the tail of the island that we needed to be able to round. I occasionally dropped off the mark, urged her back up and tried to match her fast pace. About fifty yards from the island, I could tell that I had not made myself clear: she was going to try to land on the south-facing shore of the island where waves broke against the blocks of argillite. I had not adequately explained that she would need to postpone her relief until we entered the slightly calmer conditions around the corner of the island. Even before I drew close to warn her about landing, her instincts kicked in and she began back-paddling. Gradually, she came away from the island and, sighing, followed me around the corner where we both could catch our breath, though the wind still blew.

Deep in the shadows a mule deer buck, still in velvet, foraged for still-soft greens. Sight of her first mule deer seemed to inspire her and we paddled on. Still, I had a hard time matching her pace. Eventually we rounded the gravel bar that defines the entrance to Skeeko and we relaxed inside the protection of the bay. Bodhi called out her amazement as two bald eagles circled above us.

With the lake much higher than on my paddle less than a month earlier, we pulled the boats up onto the driftwood. After we extracted ourselves from our paddle jackets it was clear that we had both worked hard. My NRS shirt was soaked, as was her long-armed bathing suit. A cooling breeze felt great. Hungry now, we lifted tuna salad sandwiches from the bear vault and agreed that a person would become strong as a bear from trying to rotate the lid past two spurs and their catch. Orange and apple slices were the perfect accompaniment to our sandwiches.

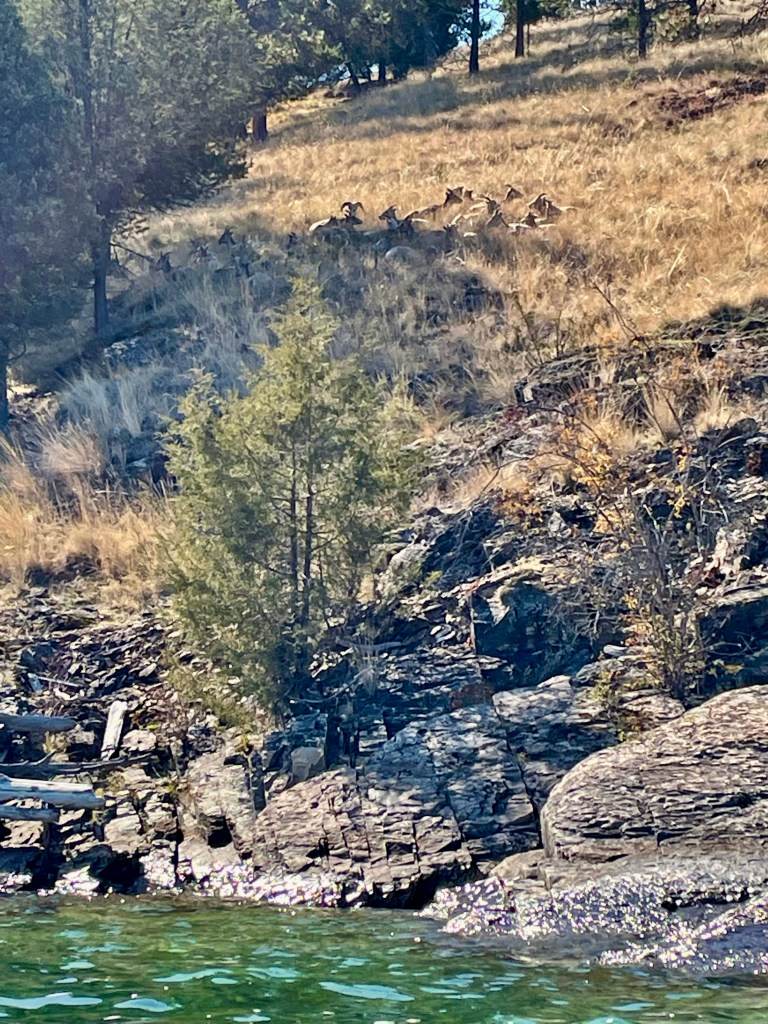

After lunch I proposed that we walk uphill to the island’s isthmus in the hope of seeing the wild horses who sometimes graze in the grass around an old and derelict corral. As though she were on the treadmill at home, she strode up the trail leaving me out of breath at the top where we paused and studied the slope below. Not horses but Rocky Mountain Bighorn sheep moved in and out of deep shadows cast by the pines. I said, “Let’s see if we can approach. We’ll use the wind in our faces to our advantage. They won’t smell us. Be sure to pause in the shade of each little cluster of trees.”

Like a huntress, she moved toward the animals who seemed nervous but did not flee. We got closer and closer until I realized that the big animals were drawn to minerals on the margins of an evaporating vernal pool. This was a magnet for them. As a wildlife biologist later explained to me, their exposure to green grass had elevated their potassium levels which could be re-balanced by consuming sodium in the drying soil.

Bodhi and I stayed outside the old fence and never blocked an opening where the rails had failed. One time the largest ram, the tips of his horns blunted by time and competition, faced us squarely and stared, setting off our own alarms. But we kept getting closer and closer until only the wire stood between us and animals we could smell. We watched for several minutes, astonished by the good fortune of having such a close encounter with animals that often elude detection.

More than satisfied, we climbed back up the slope, pausing to find a couple of tired bitterroot flowers still blooming on the hot and dry slope behind the solar outhouse. Back at the boats we enjoyed more slices of fruit and kept telling each other how lucky we were.

Though the water temperature was around 52 degrees, we knew we would stay warm while working against the wind and waves approaching us now from the southwest. I told Bodhi, partly for my own benefit, that we did not need to hurry. We needed only to paddle at a pace we could maintain as the waves, taller now, pushed against us from the starboard corner and occasionally washed over our decks. This time Bodhi took my advice, controlled her anxiety about the long crossing from island safety to the southern shore of the lake. Having learned a great deal in the morning, she remained calm in even rougher conditions, let the boat move under her and paddled just behind me as I led us back to Walstad.

After landing, reloading the boats and stowing two mounds of wet gear I felt incredibly proud of my granddaughter. This had been her first visit to Montana, her first long paddle in challenging conditions, and her first encounter with heavy-bodied wild animals. Due to the trajectories of our lives and other commitments I have never been able to give my sons this experience. But my granddaughter will carry this memory as a prize in the pocket of her vest for the rest of her life—a gift for me on Father’s Day.

Yesterday I was able to make my memorial paddle in your honor, a paddle I try to make each year between Mother’s Day and your death day in late May, now fourteen years ago. When weather and time permit, I like to make this almost-annual paddle out to Wild Horse Island on Flathead Lake, a place you always wanted to see; yet for health reasons, this visit remained an unfulfilled desire. I would like to tell you about the experience in the simply human hope that our separate worlds might touch in some way, perhaps as gently as two twigs on a cherry tree. I am still writing you an occasional letter.

When I arrived at my launch site, wind poured off the Mission Mountains and ran through the strait between Melita and the big island. Conditions were brisk but safe. After crossing the strait, I approached the island and paused to watch a couple of Bighorn ewes nibbling on fresh plants and bending to the water to drink. They were so shaggy in the remnants of their winter coats that I could not tell if they had delivered their lambs.

After paddling up the west shore of Wild Horse I rounded the point and dropped into placid conditions in Skeeko Bay. After pulling my boat onto some driftwood and out of reach of rising water, I began to hike up the trail to the saddle. I was astonished by the quiet. In the first few hundred yards I heard one meadowlark and the wings of a robin. At the saddle I turned left onto what Fish, Wildlife and Parks calls “The Heritage Trail,” a path leading to some of the last signs of a brief agricultural presence on the island. Not far along I found the horses for which the island is named, but I did not approach. One of the horses swayed in an odd fashion. As the horse was not under stress, it may have been ill.

After I gained some elevation, I chose my own path through tall grasses along the edge between meadow and forest, hoping to find an animal trail and see a greater variety of flowers. As I walked along, I picked you an imaginary bouquet. As there are no rhododendrons and roses like you grew when you lived in in the Seattle area, I found the spring blossoms of the mountain west—arrowleaf balsamroot, larkspur, lupine, long-plumed avens, camas and the occasional shooting stars on the north-facing slope and forest edge. Near the top of the island I sat down and dangled my legs over a cliff. I had a perfect vantage point to look for more Bighorn sheep if they came into the small clearing far below, but they were elsewhere and not on the move. I ate my lunch and listened to the wind.

On the way down and back toward Bluebird I found scatterings of white bones in the spaces between tall clumps of fescue. On the island deer and sheep must simply die of old age as they are rarely pursued by predators like lions and bears who visit the island on occasion. Returning to the bay I gave a pair of eagles on a massive new nest a wide berth, hoping not to disturb them. I fear they may have nested in a location too frequently visited by humans and may not be able to bring their brood to the point of fledging.

Back at my boat I changed clothes for paddling in warmer conditions but knew I would face a strong headwind. I slipped back into the water grateful for the gift of my life, that I am still able to do these things at this late stage of my own life, and that I spent another day thinking about ways you taught me to appreciate the beauty of the world without ignoring its tragedies. In whatever way such a thing could come to you, I wish you a long slope of yellow flowers and the silence of birds on the glide. Love, Gary

Early last week I sensed an opportunity to paddle. By midweek a wave of tropical moisture that substantially dampened fires north and west of Missoula headed into British Columbia and Alberta. Canadians would be as happy to receive rain as we were. The remnants of the storm made it possible for me to make my favorite paddle—an open-water crossing from Finley Point State Park to Wild Horse Island—this time with a little help from winds out of the south.

When I arrived at the campground I saw what the lake looks like when it is 2.5 feet below its normal summer level. Boaters cannot use the docks at this level, so no boats were in the marina. Beyond the nearby islands and beyond the three fingers of Rocky Point my destination appeared as a rounded hump in the distance.

I have heard people complain about the lower water level, occasionally blaming the tribes for this disappointment. In fact, the Salish and Kootenai peoples who control water releases at the dam are bound by federal contracts. In addition, they cannot be held accountable for climate change and drought, both contributors to the lower-than-normal water level.

I stowed emergency gear and lunch and made ready to paddle. As soon as I crossed the mouth of the marina I felt the corkscrew motion caused by waves slapping the port stern quarter. I paused and took the feather out of my paddle. In these conditions I did not want to stroke air while thinking I would meet the resistance of water. A flat paddle would be better, the wave motion making balance a little tricky. Having made this adjustment, I settled into ten miles of water and the rhythm of countless strokes, eventually landing at the East Shore access on Wild Horse Island. From a kayaker’s standpoint the lower water level allowed me to come ashore on a broad beach normally unavailable unless one is willing to risk paddling in the cold conditions of April.

On the comfort of a big log I ate my banana and blueberry muffin and a thick triangle of Spanish Manchego cheese. I drained my water bottle, knowing I could filter a full bottle for the return trip. While I ate my eye was drawn to a long cottonwood log. At some point in its life the wind broke off a side branch that had once been married to the main trunk. Time, water, and stones polished the soft ripples in the grain.

Though I had visited this spot several times, usually while circumnavigating the island, this time I decided to look more closely. I noticed many things I had ignored or overlooked. With the lake at a lower level I saw harder stones trapped in the mudstone ramps that once formed the floor of the lake basin and may have been part of the foundation of the mountains raised by shifting tectonic plates. I found a miniature version of the process among the countless stones on the beach.

Climbing into the forest I immediately sensed the effect of more than an inch of rain. Within a day the patient mosses had swollen and recovered. Among the mosses I found the humerus of a horse that long ago had laid down its heavy bones.

Bunch grasses were full and soft and invited me to sit down and enjoy them.

Hiking higher I saw massive pine trees thrown south by relatively recent storms. Dropping back toward the water I inspected more closely the chimney of a once splendid lodge that was built in a cantilevered fashion over the lake. The concrete had been poured against the log walls leaving horizontal flutes, and the face had been decorated with beautiful stones from the beach.

About a hundred yards away I found strands of an old telephone line, white ceramic nobs like flashlights in the forest, but telling the story of how people once communicated on the island. I also discovered a cold cellar that the lodge cook must have used to keep meat and vegetables cool for hungry guests arriving from the mainland. As the roof had fallen in, it seemed like a gateway to nowhere.

While wandering around I sensed that the wind was beginning to shift around to the north. If this change continued it would ease my paddle back to Finley Point but would again create quartering seas requiring my concentration. I went back to Bluebird, made ready, and headed home. Along the way I was careful to avoid the rocky spine now exposed at the northern tip of Rocky Point. Here the waves were actively breaking and seemed a hazard. In another hour I slipped into the marina and was relieved to be out of the rocking motion of endless waves.

Having a whole day and an evening to enjoy the experience, I put my extra food on the picnic table for an early dinner of sardines, Dakota bread from Great Harvest bakery and a crisp apple. Unfortunately, I was out of monster cookies.

Sometimes a paddle takes the form of a story. It has a trajectory, a narrative arc, and concludes with something that feels like arrival. But other times a paddle leaves one only with images, fragments and small observations that might eventually find their place in a story or simply sit in one’s memory like stones on a beach. I have learned that it is best not to force life into the form of a story. I am content with seeing clearly, looking more closely, enjoying the time we are given.

In mid-July I found two days with good, clear weather in the forecast so I made my Cedar Island overnight solo. In part I wanted to see improvements that Montana Fish, Wildlife and Parks had made on the island—a series of looping trails, tent pads marked out on the ground, and the installation of a first-rate composting toilet to prevent the fouling of the island and surrounding water with human waste. The island now awaits people willing to paddle this far, in my case, from Walstad Fishing Access to the island, or arrive under power to spend some time on an island that feels like a ship in a vast sea.

During this paddle I love adjusting myself to the multi-directional winds around Wild Horse Island—the challenge to balance and centeredness posed by crosswinds, the strength that headwinds require, the temporary pleasure of tail winds. I love the big, open-water crossing between Wild Horse and Cedar Islands that asks me to be patient and the marvelous conjunction of turquoise and cobalt water colors along the way. When setting up camp I am grateful for a hummingbird’s visit probably because I wore my red swim trunks. I am always astonished by the way they make eye contact. Sitting in my lightweight folding chair, I like watching the noise of the waves grow still around sunset. Waking in the middle of the night, I see the star river through the mosquito netting and the overhead appearance of brilliant Deneb and companion stars that form Cygnus the swan. Time on the island in a state of stillness allows me to watch two eagles race each other to a fish they spotted a half mile away, their powerful wing beats, the sudden splash, wheeling turn with taloned fish, and the long return to the roost. Time and attention are rewarded with many gifts.

This time I noticed something else. In three different locations I saw imaginative expressions of human creativity in the use of natural materials. As if undistracted by technology and its trailing devices and cords, people, perhaps children, expressed themselves in wood, stone, and bone. In the absence of civilization, with space and time to imagine, something arises in us that lies dormant during hours of attachment to our screens.

On one beach I saw the long lower jaw of a now extinct sea monster:

On another beach I found a constellation of stones and driftwood decorated with symbols and signs in waterproof paint:

In another location I found what I call a Wild Horse Still Life, an arrangement of natural objects that tells a geological story and recognizes the comparative transience of the lives of deer inhabiting the island.

Away from home and its entaglements we get playful; imagination awakens and the materials of the world present themselves, inviting rearrangement in accord with images that arise in the mind. This, too, is beautiful. This, too, is part of the journey.

Every year I try to paddle to Wild Horse Island in May. I do this to honor my mother who died this month sixteen years ago. Some people have ideal mothers. My brother and I were not so fortunate, thanks to a surgery when she was in her 20s. Medical mistakes set her up for a life of pain, chronic illnesses and multiple addictions in response to physical and mental suffering. Despite these difficulties, and partly in reaction to them, I remain the recipient of so many things. In truth my mother gave me everything I needed—a wariness of intoxicants, desire for a conscious life, my love of language, and attentiveness to the world within and around me.

Because she gave me the gift of life I am able to paddle to the island, hike its ridges, explore its valleys, appreciate its wildflowers.

Almost certainly she would have noticed and called attention to the way Balsamroot turn toward the morning light,

the composition of stone and flower, hard and soft,

an owl feather still wet with dew,

a once-living tree suspended above the current of its journey and the storms that threw it there upon the stone.

Trained by her at the window of sunrise, I notice the way cumulus clouds form the central reflection in ovoids, see the kestrel, on its perch in a pine tree, step in a full circle as it surveys the world.

Given a perfect day for paddling and a chance at life, I am nothing but grateful. In response I offer her the the whole island’s bouquet.

This week I hope to go fishing with my friend Robin. I like fishing with him because we don’t talk very much about fish; we talk about even more important things. One afternoon, for example, I remember rolling up his driveway after a day on the river and hearing him say something like, “Consciousness is the great mystery…” Maybe on Thursday we’ll return to this topic. Paddling a kayak also points toward the same mystery.

While trying to wait patiently for weather to turn incrementally warmer, I decided to repair my kayak. In the course of 16 years on the water, Bluebird’s sensitive gel coat acquired a number of scratches and dings. At the upturned end of the stern there was a spidery crack from shipping and handling, there from the beginning, a few long scratches when I did not see a sub-surface spine of sharp rock, a more serious wound received when a wave slammed Bluebird sideways into a log. To make the repairs I went to school on YouTube, bought supplies I needed from a company in Spokane, endured a little trial and error and began to make repairs before buffing the body of the boat with a series of compounds.

In the course of this project I came to appreciate how the gel coat seems as sensitive as skin and how the boat itself is actually an instrument of perception. It feels the world through which it moves as much as skin detects changes in temperature, the slightest breeze, a tender touch, puncture or scrape. In the water the kayak feels the tap of a piece of driftwood, the cutting action of a jagged rock, the friction of gravel or sand, push or slap of wave, the buffeting of headwinds, the pressure of a tail wind. As the skin perceives the outer world, so the kayak perceives the influences and effects of the the aquatic environment. This awareness motivated me to care for my boat, to try to make it last as long as possible. A boat is a story and I want to keep it alive.

To go one step farther, as I sanded the curves to get a better bond or used progressing abrasives to level the gel coat’s creamy surface, it occurred to me that the kayak actually extends my conscious awareness into the water and weather, into the liquid body of the lake, its shorelines and depths. In short, the boat is a tactile instrument that allows me to feel more than I am capable of perceiving with my mind alone. If the tip of the shovel feels the contours of the stone in the hole where one hopes to plant a tree, so the kayak extends awareness into the topography of the lake and the vagaries of weather.

If I had any doubts about this insight I would only need to recall what it feels like to paddle at night. In the absence of light the eyes are almost useless. As never before one is forced to use the body of the boat to feel the waves, the direction of their approach, their energy and strength. At night one feels—through the skin of the kayak—what is happening in the world. To the paddler’s body the kayak transmits every signal sent by water and wind.

Alert to these things, I sense how a kayak is not just a means of transport or a way to have fun on a lake but a tool that increases one’s awareness as it extends itself into the world. It is the tactile equivalent of binoculars used to focus on a vireo reaching for the last berry in a mountain ash, or a telescope turned toward a star. No wonder it seems worthy of attention and repair. Through its sensitive hull I want to keep in touch with the watery world.

Near the end of March it is still snowing, not in the fitful fashion of a spring squall but continuously, earnestly, as it usually snows in December. Once again the driveway is covered in snow and the back slope wears an armor of ice. We have been locked inside this winter for five solid months. Yet, the expansion of the light after the equinox has an effect on me in the same way that it normally affects the apple tree outside the south window. In a normal year, whatever that is, the buds would be swelling by now in response to the light if not the weather. Despite the weather, something in me is also awakening. Despite the snow and unseasonable cold, I am beginning to imagine paddling my kayak, negotiating wind and waves in a glassy vessel, exploring islands and coves, immersing myself in color, dissolving into the life of the lake.

This weather that keeps me indoors also leads me to reach toward my shelf of favorite books where I find The Living Mountain by Nan Shepherd, a slim, white paperback that stands in the company of hardbound Wendell Berry, Annie Dillard, Robin Wall Kimmerer and Robert Macfarlane. The book tells the story of Shepherd’s first sight of the Cairngorn plateau in Scotland when she was a child and how it awakened a desire to explore its heights and depths. She recounts encounters with wild weather and hardy human beings. She traverses slopes, climbs peaks, notes birds, animals and insects, crosses streams confined by granite walls, traces their courses from uppermost springs to the valleys of the Spey, Avon or Dee.

First published in 1977 by Aberdeen University Press, the book was written in the years during and soon after WWII. After Shepherd received a discouraging response to the manuscript she tucked it in a drawer where it sat untended for almost thirty years. Meanwhile she continued to climb and explore her living mountain, but also the mountain that had impressed itself on her mind and heart. In a disturbed and uncertain world the Cairngorns were her “secret place of ease.” Then as an old woman she began “tidying out my possessions,” as she says. Rereading the manuscript, she found it still valid and felt renewed energy to see it published. We are so much the richer for the second wind of this writer and her belief in what she had written.

In some ways the book resembles a kitchen pantry nearly bursting with sensory detail. As Shepherd opens the door on this pantry, she describes the taste, touch, smell, sights and sounds of the mountain in all seasons of the year, both night and day. With her description of the taste of a berry, the texture of a plant or stone, what it feels like to walk barefoot over heather, the sound of an owl landing on a tent pole or a storm crashing into the walls, canyons and corries, she practically places us inside the mountain. Then in the final chapter, acting as our mountain guide, she takes us beyond all the details of weather, the colors of leaves and feathers, the varieties of animals, the intricacies of trails and routes, human pleasures and fatalities. She leads us up and out, or down and in, until we break into the open to consider the deepest things of all, the mystery of what it means to be alive, to be aware of one’s own being in the company of Being itself. It is as if the fog and mist of sensory detail suddenly clear and in her company we see an open sky above the summit.

Rereading the final chapter of The Living Mountain I realize that what Nan Shepherd says of her beloved range might easily be said of Flathead Lake. One only needs to change a few words from her closing paragraphs to experience the lake that, like her mountain, is its own living being. If she had lived in Montana instead of Scotland, when she crested the last moraine heading into Polson she might have written:

…So my journey into an experience began. It was a journey always for fun, with no motive beyond that I wanted it. But at first I was seeking only sensuous gratification—the sensation of height, the sensation of movement, the sensation of speed, the sensation of distance, the sensation of effort, the sensation of ease: a kind of lust of the flesh, the lust of the eyes, certainly the pride of life. I was not interested in the lake for itself, but for its effect upon me, as (a cat) caresses not the man but herself against the man’s pant leg. But as I grew older, and less self-sufficient, I began to discover the lake in itself. Everything became good to me, (its long shoreline, its islands, its rocky hillsides and forests, its shades of color, its crevice-held flowers, its birds). This process has taken many years, and is not yet complete. Knowing another is endless. And I have discovered that the experience enlarges (the ramps and slabs of stone, deep, dark depths, turquoise shallows, great banks of gravel, deer and sheep drawn to the margins). The thing to be known grows with the knowing.

I believe that I now understand in some small measure why the Buddhist goes on pilgrimage to a mountain (lake). The journey is itself part of the technique by which the god is sought. It is a journey into Being; for as I penetrate more deeply into the (lake’s) life, I penetrate also into my own. For an hour or two I am beyond desire. It is not ecstasy, that leap out of the self that makes a human like a god. I am not out of myself, but in myself. I am. To know Being, this is the final grace accorded from the (lake).

I do not know when this storm will end, when the ground will thaw, when the water temperature will rise enough to make paddling seem safe. But as the light changes, whatever atmospheric rivers flow our way, I imagine what it will be like to be on and in the living lake. Like Shepherd the hiker and climber, walking herself “transparent” to every living thing in her world, I hope to paddle myself transparent, clear of fears and concerns, empty of self, open to every resonating thing in a still-living world. As Shepherd’s knowledge of the mountains evolved, so, too, has my motivation and knowledge of the lake evolved. I will return to the lake not for myself but to experience the lake being itself.

I sometimes ask myself, Why do I do this? Why drive 160 miles round trip to get wet, windblown or sunburned? Why burn about six gallons of gasoline at a time when we are warming the planet faster than it can absorb the carbon dioxide we produce? Why deal with the aggression on the highway of the big-truck crowd? Why do this when so many things demand attention at home, especially in October when we are trying to finish outdoor chores before winter slams the door on light and comfort?

Midway through my paddle out to and around Wild Horse Island I realized a couple of possible answers to my questions. On September 15, I tested positive for the Omicron variant of the Covid 19 virus. My case was relatively mild compared to others whose coughs linger for weeks, who lose taste and smell, who suffer lasting fatigue, or even die. Paddling against a north wind reminded me that I have recovered, that my body has restored itself to health. In the two-hour beat against the wind, without distraction and in the company only of my thoughts, I remembered something else. On a recent visit to see my youngest son and his family I told Kyle that getting older does not necessarily mean things get easier. He looked at me squarely as we hugged one last time at the airport and said, “Stay strong, Dad.” I think he was telling me, “Dad, I need you in the world. Stay active. Don’t leave too soon.” Perhaps I drove north and paddled north for these reasons—to celebrate the recovery of health and as part of the process of staying strong for those who need me in the world.

In my circumnavigation of the island I looked to Osprey Cove as a refuge where I hoped to rest and eat lunch, but the landing did not feel safe; waves had pushed the gravel into a steep and sliding slope. I backed out of the cove and headed south where I hoped to find a more protected place to land. I found such a spot at the East Shore access to the island. I got out of Bluebird without spilling and wedged the boat between two drift logs. Thanks to my beloved I enjoyed a massive and spicy Beach Boy sandwich from Tagliare and Smyrna figs. After lunch I wandered the shoreline, climbed into the dry grasses and yarrow. Along the way I discovered a Big Horn sheep skeleton, bleached and barren. I took time, too, to marvel at the clear water of October, all the sediments and pollen settled out. At this point in the season the water seemed like a pure distillation. Once back in my boat I continued south, avoiding the ramps of stone along the shore because the reflected energy of waves created rougher conditions a few yards off shore. When I saw sheep resting in the shade of a pine tree, however, I could not resist approaching for a photo. I rarely see these animals in the open. This was their time to build reserves before winter makes life more difficult.

At the south end of the island I turned west and enjoyed several miles of assisted paddling as wind and waves nudged me from behind. In the face of things I felt I should do, I left home, but returned feeling as though my body had been washed clean as October gravel near shore. The lake offered an image to the imagination. This is something to celebrate.