I was determined to go paddling before the thermometer popped the 100-degree mark, before fires grew worse and the air became unhealthy from fires to the west and south. Having paddled in honor of my mother in May, and having introduced one of my granddaughters to the lake and its largest island in June, I wanted to paddle within myself in July, returning to places that are no longer new.

With the smoke in a blue-gray band above me, I stroked out of the marina at Finley Point, made a right turn and headed for Bird Island. I quickly fell into that beautiful rhythm of harmonious breathing timed to the pace of my strokes. Though I have made this paddle countless times, something about the island was different. Through the haze I could see that Montana’s Fish, Wildlife and Parks had installed a solar toilet near the south end of the island, above the beach where many people come ashore. I applaud their decision to reduce waste on the fragile island. Continuing north I saw the black blocks of stone that mark the entrance to one of my favorite coves near the opposite tip of the island. Rounding this angular corner I saw a cove I hardly recognized. Instead of a little bay with an incredible view and an accommodating beach, this half circle of shelter was choked with logs that had washed down from the north, trees that had fallen since the island burned, a massive, bleached post, and lots of lumber ripped from docks, nails in the air. There was barely enough room to slide my kayak into a secure position while I walked over the debris and dove into the water from one of the blocks of stone.

Refreshed by my plunge and a little hungry, I ate a peanut butter and jelly sandwich and a couple of delicious rolls of baklava left over from a party we attended Sunday night. Since the lake was calm and with no change in the forecast, I decided to try something I had never done before—paddle from Bird Island across the width of the lake to Wild Horse Island. As often as I have paddled to Wild Horse, I had never made this eight-mile crossing. I drank half a water bottle charged with electrolytes and settled into a sustainable pace. In the thick haze it was hard to pick a target that would keep me moving in a straight line, but I aimed for a faint wedge of shade on the northeast corner of the island.

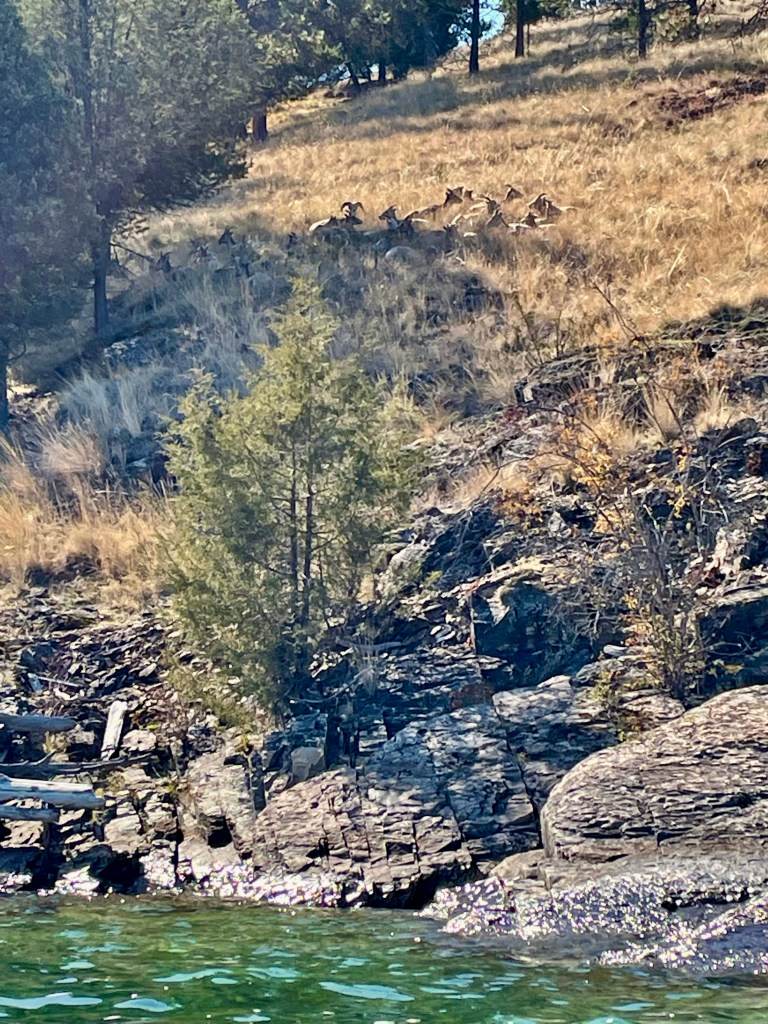

The miles seemed to fly by as I concentrated on rhythmic strokes. In mid-July the surface of the lake is usually clean; pollen has settled onto the bottom and tree roots and branches have come ashore. But this year the surface of the lake was covered with a yellow substance that I first thought was pollen, but then realized was dried algae. Throughout the crossing I made small adjustments to my course to avoid floating woody debris, branches, roots and bark. Eventually, it dawned on me that this year’s high lake level had lifted material from beaches and riverbanks across the watershed and set it in circulation. This was a different lake surface.

When I finally landed in a small indent on the east shore, I was sweaty from the effort. Not hearing the sound of boats and their engines, I stripped my clothes, left them to dry on hot stones and made a few breaststrokes out into the viridian. I thought to myself, all of us should swim naked more often and not leave this experience to children exploring water for the first time.

Curious about this part of the island, I dressed again and began to explore the forest above the narrow beach. I found a premier pink Mariposa lily. Having once found several white ones, I regretted having once mislabeled this plant as a sago. I also found a dead raven. Though I could not be sure–since the breast of the bird had not been consumed—I wondered if the big black bird had been knocked out of the sky by the fist of an eagle.

Back at the beach I found half of a broken stone that because of its color and dimensions reminded me of a cookie, but then found its other half in another location. I tested the fit and found it perfect. I think I have an eye for cookies. Together the stones reminded me of the ancient Jewish practice of cutting a covenant or the practice in English jurisprudence of cutting a contract. Once again, I realized that a familiar place seen with fresh eyes can be full of discoveries.

I returned to Bluebird, ate a wedge of my favorite Manchego cheese, salty crackers and the last of my baklava. In planning my return to Finley Point I decided to paddle down the east shore, cross to Matterhorn Point, then Black Point, the east side of the unnamed island in The Narrows, then cross to the last spindly cottonwood marking the mouth of the marina at Finley campground. This route would give me a brief period of shade every time I passed a point or island. In the heat of late afternoon I craved shade. I added sunscreen, filtered another bottle of water, ate a dried apricot or two, and settled into the next leg of my journey.

When I finally landed at the concrete boat ramp at the marina a woman came rushing up to me.

“Was that you way out in the middle of the lake? We watched you come across.

“Yes,” was all I managed to say, tired from almost 27 miles of paddling and not quite ready for human interaction after seven hours of solitude.

Strangely eager, she asked, “Would you like some help lifting the boat out of the water?”

Never before had I accepted such help, but conscious of many new things in a place that has become familiar, I stretched myself and said, “Sure. That would be wonderful, but we need to set the boat on the grass so I can unload my emergency gear.”

This friendly and strong woman seemed to enjoy offering this assistance and I confess to being grateful for her help. After we set the boat away from the concrete she said, “My husband and his friend will come over and help you lift your boat onto the saddles of the rack.” Not quite at ease with this change in myself, I simply said, “Great.”

I piled wet gear, emergency bag, phone in its Pelican case, and first aid supplies in the bed of the truck. Turning around I saw two guys coming toward me asking for directions. One carried my Greenland paddle that I had tossed on the grass. The other lifted the bow into the back saddle and helped me slide the boat forward into place. It was a joy to have help. This was as much a discovery as the changes to my favorite cove, the pink lily and the raven. All that was new was beginning to find a place in a life I know by heart.